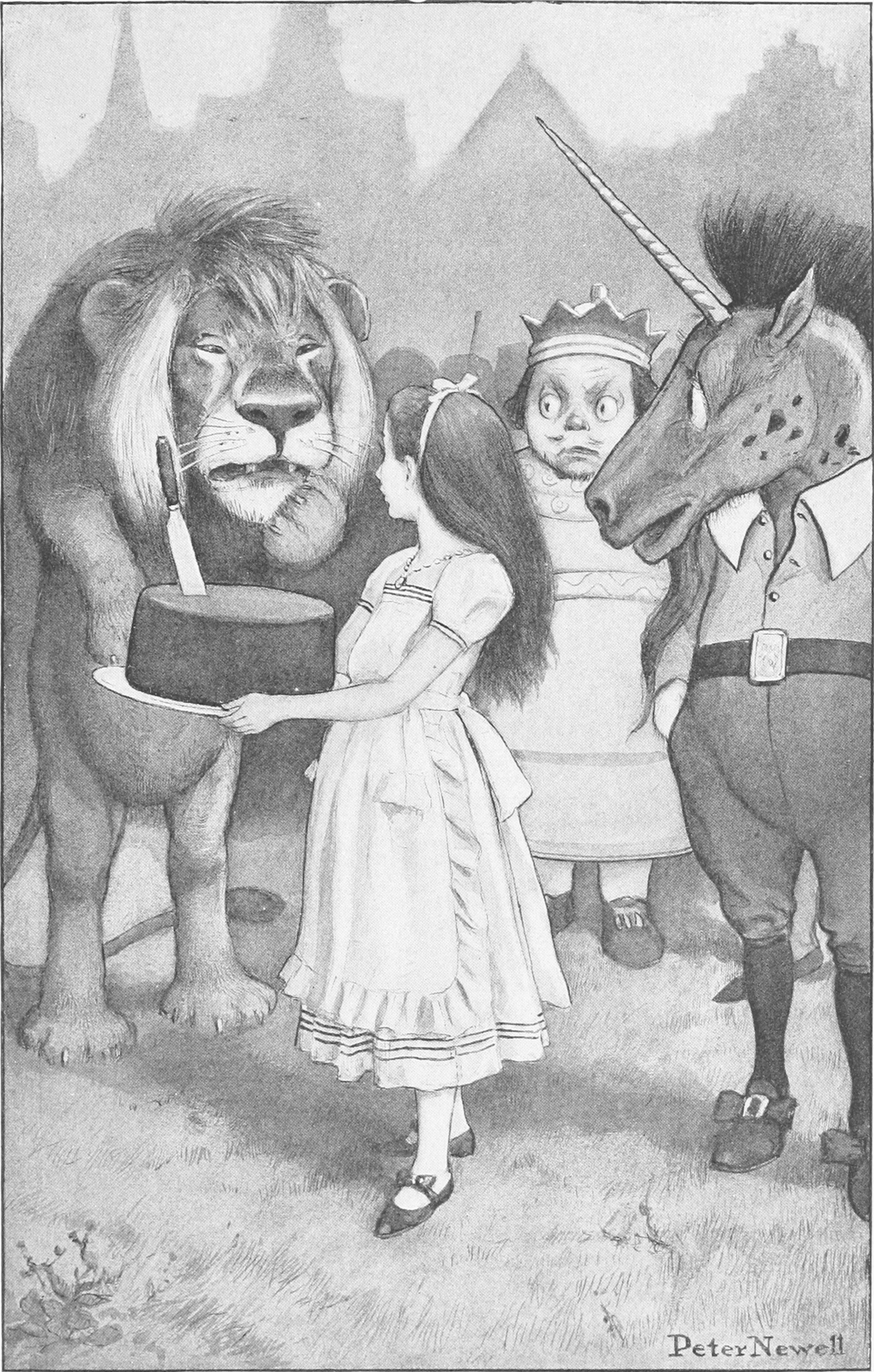

In Chapter VII of Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There, the Unicorn looks at Alice “with an air of the deepest disgust” and asks, “What – is – this?”

“This is a child!” Haigha replied eagerly, coming out in front of Alice to introduce her, and spreading out both hands toward her in Anglo-Saxon attitude. “We only found it to-day. It’s as large as life, and twice as natural!”

“I always thought they were fabulous monsters!” said the Unicorn. “Is it alive?”

There’s layers of good jokes here, as the Unicorn thinks Alice is a “fabulous monster,” and then offers to believe in her if she believes in him. There’s also some play on the concepts of “life” and being “alive.” (Death is one of the major themes of TTLG.) For Haigha’s “twice as natural” remark, Martin Gardner’s note in The Annotated Alice is this:

“As large as life and quite as natural” was a common phrase in Carroll’s time (the Oxford English Dictionary quotes it from an 1853 source); but apparently Carroll was the first to substitute “twice” for “quite.” This is now the usual phrasing in both England and the U.S.

This series G.A.H.! (Gardners Annotations Hyperlinked) has the singular purpose of supplying internet links to Martin Gardner’s classic notes. Since he wrote them more than fifty years ago, some of his sources have become difficult to find in print, or alternately, easier to find online. Gardner never cites why he thinks Carroll was the first man to change the “quite as natural” into “twice as natural,” although it is vintage Carrollian wit. No doubt the inclusion of the phrase in the Alice books has aided its longevity in that form.

It’s hard to create hyperlinks for the Oxford English Dictionary. The OED is ubiquitous in halls of higher learning and prohibitively expensive to access outside of them. My local public library doesn’t have a subscription, so I had to swim through their physical volumes to find where and what that 1853 source was that Gardner referred to. I found the quote in question under life s.b., on page 911 in Volume VIII of the Second Edition:

7. a. (In early use commonly the life.) The living form or model; living semblance; life-size figure or presentation. Also life itself. after, from (or by) the life: (drawn) from the living model. as large as (the) life, life-size; hence humorously, implying that a person’s figure or aspect is not lacking in any point. Hence larger-than-life; larger-than-lifeness (nonce). small life: ? somewhat less than life-size.

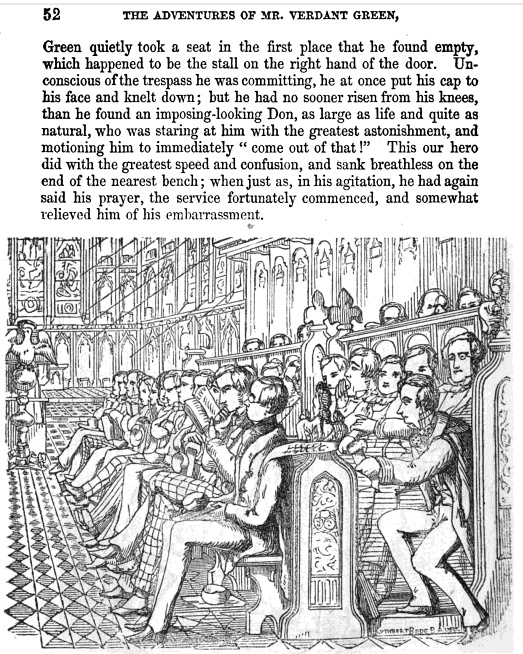

There’s nothing like needing a dictionary to have a joke explained. “As large as life” is funny because, you see, in a humorous context, you are implying that the life-form has successfully achieved an adequate fullness of size in proportion vis-à-vis its life. They supply several quotes about the size of life, many much earlier than 1853. The 1853 quote that Gardner alludes to is from ‘C. Bede’ Verdant Green, I. vi. “An imposing-looking Don, as large as life, and quite as natural.” I can create a hyperlink for The Adventures of Mr. Verdant Green by Cuthbert Bede, B.A., a novel about a Freshman undergraduate at Oxford University (written within a few years of when C.L. Dodgson entered Oxford). The full text is at Project Gutenberg and the 1857 edition can be seen on Google Books, with 90 illustrations by the author, (whose real name was Edward Bradley).

Now, the Second Edition of the OED wasn’t published in its glorious twenty volumes until 1989, so the First Edition that Gardner would have looked at (in the early 1960s) might not have included the following quote, which is in the Second Edition immediately before the 1853 C. Bede one:

1840 Lady Wilton Art of Needlework xxi. 334

Birds … being, in proportion to other figures, certainly larger than life, and ‘twice as natural’.

What happened? Lady Wilton’s quote uses Carroll’s ‘twice as natural’ instead of the “common phrase” ‘quite as natural,’ and 1840 is three decades before Looking-Glass was written.To further add to the mystery, she places “twice as natural” inside inverted commas, to imply she’s also quoting something earlier – but what? (As for the “larger then life” versus “large as life” debate, there’s an article in the New York Times Magazine by William Saffire published October 14, 1990, about the evolution of the phrase. The article includes a conversation with Charlton Heston, who had nitpicky opinions about which of his characters were “as large as life” and which were “larger than life.” Henry VIII? Merely as large as life. Long-John Silver? Larger than life.)

Project Gutenberg also has the text of “The Art of Needle-work, from the Earliest Ages” (1841) which was edited by “The Right Honourable The Countess of Wilton” (actually named Elizabeth Stone), and Google Books also has one of their Xerox-quality scans of the 1841 edition. Wilton uses the expression twice in this book. In a chapter called “The Needle,” she tells a weird anecdote about an old woman’s needle, and the phrase “large as life and twice as natural” refers to a tear-drop found in the needle’s eye. I’ll quote it in full for context and also because it’s very silly:

For instance, we were told of an old woman who had used one needle so long and so constantly for mending stockings, that at last the needle was able to do them of itself. At length, and while the needle was in the full perfection of its powers, the old woman died. A neighbour, whose numerous “olive branches” caused her to have a full share of matronly employment, hastened to possess herself of this domestic treasure, and gathered round her the weekly accumulation of sewing, not doubting but that with her new ally, the wonder-working needle, the unwieldy work-basket would be cleared, “in no time,” of its overflowing contents. But even the all-powerful needle was of no avail without thread, and she forthwith proceeded to invest it with a long one. But thread it she could not; it resisted her most strenuous endeavours. In vain she turned and returned the needle, the eye was plain enough to be seen; in vain she cut and screwed the thread, she burnt it in the candle, she nipped it with the scissars, she rolled it with her lips, she twizled it between her finger and thumb: the pointed end was fine as fine could be, but enter the eye of the needle it would not. At length, determined not to relinquish her project whilst any hope remained of its accomplishment, she borrowed a magnifying glass to examine the “little weapon” more accurately. And there, “large as life and twice as natural,” a pearly gem, a translucent drop, a crystal tear stood right in the gap, and filled to overflowing the eye of the needle. It was weeping for the death of its old mistress; it refused consolation; it was never threaded again.

In that instance also, the idiom is in quotation marks, as if she’s either quoting a common phrase or referencing a well-known joke from an unnamed source. Seventy-nine pages later, in an unrelated context, the Countess of Wilton is describing French tapestries. The images are “representing scenes of the chase, and are enlivened with birds in every position, some of them being, in proportion to other figures, certainly largerthan life, and ‘twice as natural.’” The italic emphasis on “larger” is hers, indicating that she’s playing around with the phrase “as large as life” – the birds depicted on a giant tapestry, you see, are indeed larger than real-life birds. They’re also twice as natural. Vintage Wiltonian wit.

Brilliant!